Brief History of the city of Madrid

Alfonso VI in Madrid The date of Alfonso VI’s entry is cited between 1080 and 1090 and in this attack comes the nickname for Madrid’s citizens today “gatos” (cats because they climbed the walls). Two different cultures, the feudal and the Islamic, existed. There is no mention of massive emigration, but a royal document ruled: the distribution of population: the Jews and the Moors were to be grouped together in las Vistillas (where the Christians were before). However, the three cultures still lived together peacefully, and the administration of the medina, each district, souqs and baths continued. The social structure was established according to jobs and classes. Madrid was still the “Ribat”, with a communication centre with watchtowers. The main mosque was dedicated to Santa María. The legends surrounding the vision of an image of the Virgin on the outer wall on 9 November 1085 also date back to this era. This is the image of the Virgin of Almudena, patron saint of Madrid.

S. Isidro was born on 1082 and died on 30 November 1172. He is the city’s patron saint and was a great devotee of the Virgin of Almudena. Madrid consolidated its status as a city and a Castilian community. The majority of researchers place the known remains of the second walled enclosure at that time. It covered an irregular surface area of 33 hectares from the first enclosure to Puerta de Moros-Puerta Cerrada (where there is still a mural today with Madrid’s original maxim: It was built on water) and Puerta de Guadalajara-Puerta de Balnadú-Alcázar. According to Jerónimo de la Quintana, it was made of chalk, stone and mortar, 12 feet wide, and had towers, barbicans and ditches of water, this is the origin of the name “cava” given to several streets, as it was constructed on this filled ditch). If we read the municipal charter of 1202, we see that the wall was still being built.

Arab domination

Madrid became important under the Arabs. Initially Toledo was the most important city in the meseta, however to defend it, they looked to the small village on the banks of the Manzanares and built a fortress on the hill where the Royal Palace now stands.

At the end of the XIX century, the emir Muhammad I (852-886) founded the city of Mayrit as an “almudayna” (fortress). The name seems to come from the numerous streams carrying water to the area and known as machra (matrice in Latin), which changing the suffix to –it, becomes Machrit meaning a place that receives a lot of water (for the Christians it became Magerit).

The emir, in fact, simply walled an earlier area, which could have been at least Visigothic, as there was a village probably situated on the steep riverbank of calle Segovia (down which the river matrice, mother of waters, flowed). He wanted to make the city stand out, and therefore built the palace with its outbuildings (governor’s residence and a mosque) on one of the hills next to the steep riverbank, thereby establishing the fortress. Then he walled it with blocks of stone “stretcher and header”, using silex or flint for the lower part and limestone for the upper part, surrounding it with ditches full of water (“cavas”) from the abundant streams in Madrid. “Built on water were my walls of fire” as we are reminded from the mural that has decorated one of the medians of the closed doorways, since the 80’s, reproducing an ancient emblem.

This citadel was an irregular square shape and covered little more than 4 hectares. Outside the walls lay the “vega” (fields of crops between the city and the river) and the “almuzara” (public land for leisure and equestrian sports). Madrid’s growth was unexpected and the inhabited area expanded past the Islamic wall to the east. The suburb of Axerqua, the settlement to the south which is now las Vistillas (where the Mozarabs went to live), and the parish of S. Andrés are already mentioned in medieval documents.

According to some, the walled area also included these settlements, thereby forming a village with two hills and a steep riverbank in between, all of which were fortified. Nowadays, it is thought that the known remains of the second enclosure date back to just after the Spanish conquest. These two enclosures are very important because the village became a closed town, and its inhabitants were already aware of being in a city since they had a main mosque or “aljama” (on the corner of what is now calle Mayor and calle Bailén), walls, and a fortress or “almudayna”.

In about the C10 madinat Mayrit is frequently cited as a “ribat” or border post. Moslem chroniclers emphasize its fortification and its city status. Towards the end of the X century (932) Ramiro II seiged the city with five hundred horsemen, entering, by the grace of God, via a breach. Two years later the first caliph of Cordoba, Abderrahman II, reconstructed the fortifications as he considered them to be of great strategic value. Culture flourished in Madrid. It was the time of the Seven Schools of Astronomy and Abu-I-Qasim Malsana Al Mayriti (the man from Madrid), one of the most important astronomers of Al Andalus. In the XI century Madrid formed part of the kingdom of the Taifas in Toledo. In 1047 there was a supposed expedition of the king of Castille Fernando I, but it was returned to Toledo in exchange for a tribute.

During this last phase of the Islamic domination, some claim the walls were extended, which would make the city conquered in 1085 very similar to that of the XII and XIII centuries, where growth was concentrated in the suburbs and the perimeter was only extended to the north with the construction of a new palace built outside the walls.

In 1050 the Christians of the medina pay homage to the body of San Isidoro of Sevilla, on its way to Leon where he was finally buried.

Prehistoric and Roman periods

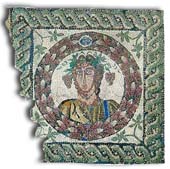

There are only a few remains of “carpetana” ceramics and Roman “sigillata” ceramics, funerary steles (which would have been on the steps of Santa María church, and fragments of mosaic flooring from the protohistoric and Roman periods kept in the Municipal Museum that confirm the romanization of the area. It is claimed that the town mentioned on Antoninus Pius’s route called Miaccum (from the Hebrew Miakud, becoming ex incendio in Latin) which ties in with some interpretations that refer to Madrid as being encircled by fire because its walls were made of flint, or as the poet called it the Osaria surrounded by fire and set on water. This must have been set in Madrid and linked to the place-name of Meaques. It is thought that it must have been near the right banks of the Manzanares (the name of which derives from Miaci-Nahar, Miacum river, although it could also derive from Man-Nahar, river of sustenance).

It is also said that during the Roman domination Madrid was given the name of Ursaria (either derived from the Latin ursus, owing to the large number of bears there – which would eventually form part of its emblem – or else from the Hebrew word Ur, meaning fire which would tie in with the meaning of Miacum), later becoming Maioritum, indicating that it had grown. Following this theory and based on the characteristics of the wall surrounding the hill fortress (location of the Royal Palace), which was the second wall, it is said to be from the Roman period. In fact Maioritum is only the Moorish Magerit latinized in documents after the conquests, and which had variations such as: Mageridum, Magritum, Matritum… Subsequently the Visigoths arrived, however, we only have gold jewelry from them. There are no documents or buildings.

Foundation of Madrid

The foundation of Madrid is debated between legend and history. According to D. Ramón de Mesonero Romanos (the city’s first official chronicler): “Madrid has admirers who have sung its praises and tried to date its origins as far back as mythological heroes.” From the XVI and XVII centuries, as a result of the transfer of the Capital, Madrid’s chroniclers wanted to give it an ancient lineage going back ten or more centuries before Rome was founded, a few years after the world flood, meaning it would have been in existence for over 4,000 years. These same chroniclers, plagiarizing Virgil’s origins in the Italian city of Mantua, declared that Madrid was founded by the Greek prince Ocno-Bianor, son of Tiber, King of Tuscany and the divine Manto, and was named Mantua in his honour. (In fact “carpetana” Mantua according to its position in Ptolemy’s charts would be Talamanca, not Villamanta as several people claimed). Others believe Madrid has Greek origins, basing their theory on the figure of the sculpted dragon in Puerta Cerrada.

If a city has no history until it is documented, we can only make references based on writings or else archaeological remains. In this way we can trace its beginnings back to the banks of the River Manzanares in prehistory (in the tertiary period, about 20 million years ago). However, the remains found from this period are only fossils of large animals, the most important of which were discovered in what is now Paseo Imperial and Paseo de las Acacias. The first human remains correspond to the early and mid Paleolithic periods (approximately 500,000 years ago) and were dug up on the terraces of the Manzanares (Cerro de San Isidro). Although if we keep to the materials that appeared in excavated pits at Cerro de San Andrés, near the river running down what is now Calle de Segovia, the towns as such in the area of present-day Madrid during the late Middle Ages should not have been there until the Bronze Age (two thousand years BC). This early town is quite logical as they had woods, animals to hunt, water, and flint to make their weapons.

In 1993 the archaeological and pale ontological heritage of this area, covering both banks of the river (Terrazas del Manzanares), became protected as an area of Cultural Interest.

The XII Century, New Arab Conquest

At the start of the CXII following the death of Alfonso VI, Alí ben Yusuf (1109), an Almoravid king, attacked and conquered the village, the outer wall and the medina. However, the palace, defended by the inner wall resisted and finally, thanks to the plague which hit the Arabs obliging them to withdraw to Seville, Madrid’s citizens were able to leave the palace. Five years later the attack was repeated from Campo del Moro.

Alfonso VII finally reconquered Madrid. He gave his letter of consent (first indication of his future municipal charter), authorizing in 1129 the population of S. Martín district around the Benedictine monastery of the same name – which would now be in c/Arenal – leaving the Jews, Arabs and Moors between two populated areas. In the 50’s came the privileges of Alfonso VII: cession of Dehesa de la Villa, rights to pastures and firewood, the possession of Real del Manzanares… The walls were extended to take in the suburbs of the former medina. The last attack on Madrid occurred in 1197.

XIII Century

THE XIII CENTURY. CXIII. The Council or City Community and Villages within the city walls, were given a Municipal Charter in 1202 during the reign of Alfonso VIII of Castille, enabling them to make use of the land and woodland of Madrid up to part of the Sierra.

That same year a dispute began between the city and the city council about the possession of pastures, land, trees and hunting in certain woodland. It was settled in 1222 with both parties agreeing that the church should keep the pastureland and the council the trees. To ratify this agreement, the Council adopted a shield with a climbing bear, and the Clergy a she-bear walking (despite the fact the previous emblem of the city, worn by Madrid’s militia in the battle of Navas de Tolosa, showed the she-bear walking and apparently the seven stars of the Ursa Minor on its loin).

The name of “city of the Bear and the Strawberry Tree”, owing to the abundance of both in the surrounding woodland, dates back to the XIII century. Although in the different manuscripts it is a she-bear and not a male bear. According to the Archives, the position of “Justicia Mayor de Madrid” (predecessor of the subsequent chief magistrates and mayors) as held by Rodrigo Rodríguez already existed in 1219.

Madrid became fully established as a Castilian city.